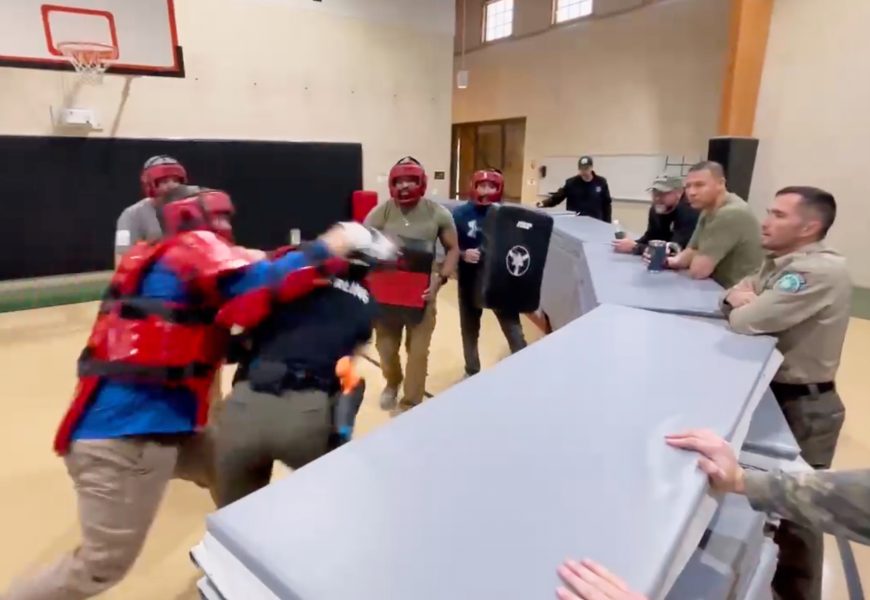

When recruits were repeatedly punched and tackled during a role-playing exercise at the Texas game wardens academy last year, they were taking part in a longstanding police training tradition that critics say should be retired.

How a violent police academy drill has been tied to deaths and injuries across the country

When recruits were repeatedly punched and tackled during a role-playing exercise at the Texas game wardens academy last year, they were taking part in a longstanding police training tradition that critics say should be retired.

By the end of the day, at least 13 of the cadets reported injuries. At least two concussions. A torn knee. A bloody nose. A broken wrist. Two would need surgery. One would resign in protest. Another quit even before the drill.

A state investigation later found nothing wrong with the drill, which its supporters say is intended to teach recruits to make good decisions under intense physical and mental stress. The experience on Dec. 13, 2024, may have been traumatizing for some at the Texas Game Warden Training Center in Hamilton, Texas, but it was not unique.

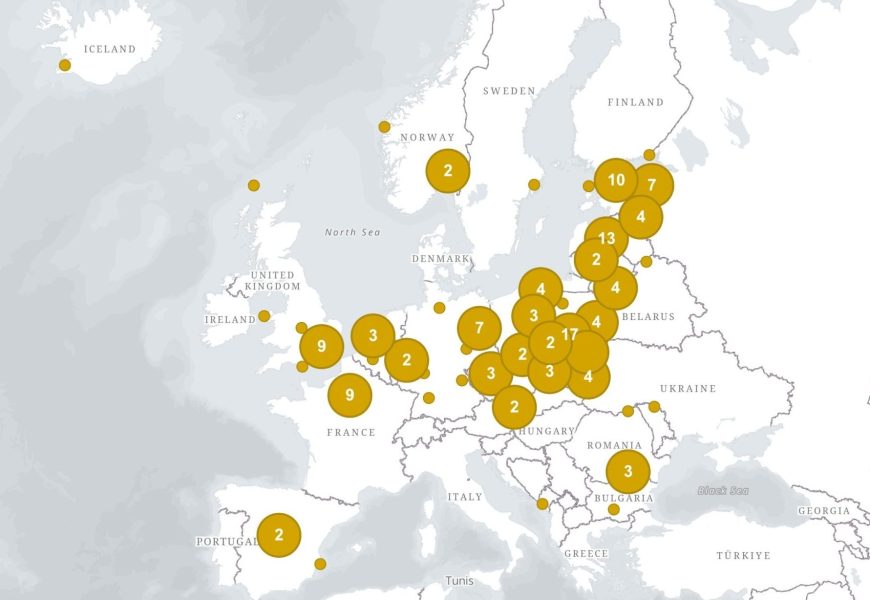

Since 2005, drills intended to teach defensive tactics at law enforcement academies have been linked to at least a dozen deaths and hundreds of injuries, some resulting in disability, according to a review by The Associated Press.

The drills – frequently referred to as RedMan training for the brand and color of protective gear worn by participants – are intended to teach law enforcement recruits how to defend themselves against combative suspects. They’re among the most challenging tests at police academies. Law enforcement experts say that when properly designed and supervised, they teach new officers critical skills.

But critics say they can put recruits at risk of physical and mental abuse that runs some promising officers out of the profession. Academies have wide latitude in running such exercises, given a lack of national standards governing police training.

Here are some takeaways from AP’s report.

A string of tragedies across the nation in recent years has brought new attention to the details of curricula at law enforcement academies.

In August, 30-year-old Jon-Marques Psalms died two days after a training exercise at the San Francisco Police Department Academy. He suffered a head injury while fighting an instructor in a padded suit.

An autopsy found his death was an accident caused by complications of muscle and organ damage “in the setting of a high-intensity training exercise.” His family has filed a legal claim against the city and hired experts for a second autopsy.

In November 2024, a 24-year-old Kentucky game warden recruit died after fighting an instructor in a pool to the point of collapse, video obtained by AP shows. William Bailey’s death was ruled an accidental drowning due to a “sudden cardiac dysrhythmia during physical exertion.”

A year earlier, a Denver police recruit had both legs amputated after a training fight that his attorney called a “barbaric hazing ritual” left him hospitalized. An Indiana recruit died of exertion after he was pummeled by a larger instructor, and a classmate was disabled after fighting the same man.

Academies have discretion to design training within state guidelines, and AP found the drills take many forms at local police, county sheriff and state departments. They’re sometimes called “combat training,” “Fight Day” or “stress reaction training.”

Some recruits have to ward off several assailants at once. Others fight a series of instructors, one after another. Some academies intentionally use larger, more skilled instructors. The stated goals are generally the same: to use skills learned in the academy to fend off or subdue assailants and to never give up.

Recruits and instructors wear protective gear to cushion their heads from blows. But there are no uniform safety guidelines, including whether academies must have medical personnel on site.

One of the recruits injured last year was Heather Sterling, a former Wyoming game warden who had moved back to her home state of Texas to continue her career.

Sterling had been a defensive tactics instructor in Wyoming before enrolling in the Texas academy, and she was concerned when she learned about the so-called four-on-one drill.

During the exercise, cadets faced a barrage of attacks from four instructors playing the role of violent assailants. Cadets would have to kick and punch a bag held by an instructor and try to fend off attacks for 90 seconds or more.

Sterling thought the scenario was unrealistic. She said she had never been ambushed on the job, and she would be able to use her firearm or other force if that happened in real life.

Video shows that Sterling was punched seven times in the head in less than two minutes, and the last blow knocked off her wrestling helmet. She was also thrown to the ground.

Sterling said she had a pounding headache, and later drove herself to get medical treatment. She was diagnosed with a concussion.

Sterling passed the drill but resigned from the academy in protest. Now she’s speaking out in the hopes of bringing change to practices in Texas and elsewhere.

“I’m worried that someone is going to get killed,” she said. “This is a poorly disguised assault.”