TALLINN, Estonia (AP) – The only official document human rights advocate Uladzimir Labkovich had with him when he was suddenly released from a Belarus prison, blindfolded and driven to neighboring Ukraine was a piece of paper with his name and mugshot on it.

Prisoners freed by Belarus say their passports are taken away in a final ‘dirty trick’ by officials

TALLINN, Estonia (AP) – The only official document human rights advocate Uladzimir Labkovich had with him when he was suddenly released from a Belarus prison, blindfolded and driven to neighboring Ukraine was a piece of paper with his name and mugshot on it.

“After four and half years of abuse in prison, I was thrown out of my own country without a passport or valid documents,” Labkovich told The Associated Press by phone from Ukraine on Wednesday. “This is yet another dirty trick by the Belarusian authorities, who continue to make our lives difficult.”

Labkovich, 47, was one of 123 prisoners released by Belarus on Dec. 13 in exchange for the U.S. lifting some trade sanctions on the authoritarian government of President Alexander Lukashenko. All but nine were taken to Ukraine; the rest – including Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski – were driven to Lithuania.

A close ally of Russia, Lukashenko has ruled his nation of 9.5 million with an iron fist for over three decades. Belarus has faced years of Western isolation and sanctions for its crackdown on human rights and for allowing Moscow to use its territory in the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Recently, Lukashenko has sought better relations with the West, releasing hundreds of prisoners since July 2024.

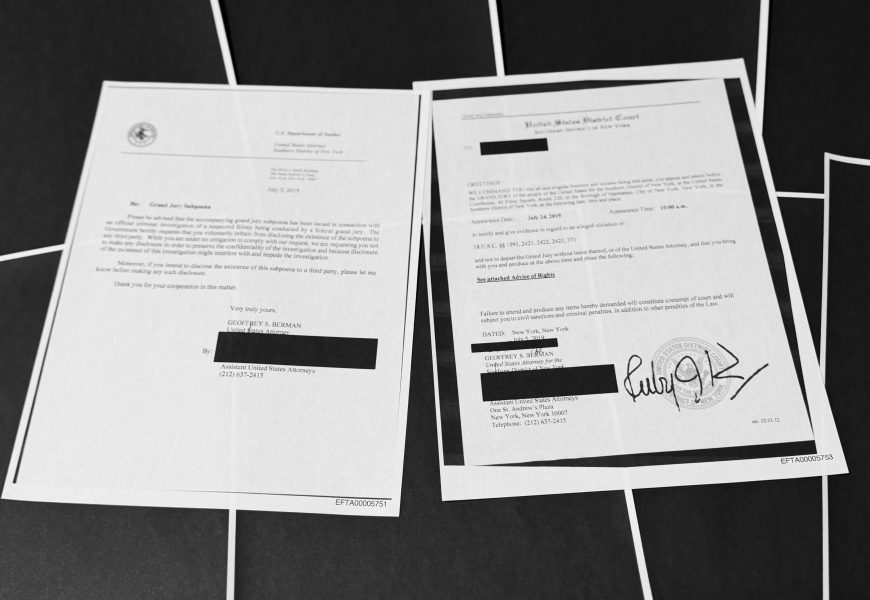

But in a final act of indignity and repression, the newly freed prisoners often are not told they are being deported without passports or other identity papers. They must rebuild their lives abroad, facing bureaucratic obstacles without any help from their homeland.

Because he was blindfolded, Labkovich said he and others could only tell they were heading south. At least 18 prisoners taken to Ukraine – including Labkovich and Belarusian opposition figures Vitkar Babaryka and Maria Kolesnikova – had no documents with them, according to rights advocates. Germany has promised to provide shelter to Babaryka and Kolesnikova.

“I dream of hugging my three children and wife in (the Lithuanian capital) Vilnius, but instead I have to deal with absurd bureaucratic procedures,” Labkovich said.

Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who fled the country in 2020, told AP in written comments that the way the prisoners were taken out of Belarus was “a forced deportation in violation of all international norms and regulations,” adding it was inhumane treatment.

“Even after pardoning people, Lukashenko continues to retaliate against them,” Tsikhanouskaya said. “They bar people from staying in the country, they forcibly drive them out of Belarus without documents in order to humiliate them even further.”

In September, Lukashenko pardoned more than 50 political prisoners who were taken to the Lithuanian border.

One of them, prominent opposition activist Mikola Statkevich refused to leave Belarus. The 69-year-old, who called the government’s actions a “forced deportation,” pushed his way out of the bus and stayed for several hours in the no-man’s land between the borders before being taken away by Belarusian police and returned to prison.

Fourteen others who had crossed into Lithuania from the September release didn’t have passports. Freed activist Mikalai Dziadok said Belarusian security operatives tore up his passport in front of him. Freed journalist Ihar Losik said all of his papers – including diaries – were confiscated.

“My passport was simply stolen. We came here (to Lithuania) – no one had passports. They took photos, all papers, the verdict, notebooks – they took everything,” Losik said.

Nils Muižnieks, the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights in Belarus, described what happened to the prisoners as “not pardons, but forced exile.”

“These people were looking forward to returning to their homes and families,” he said in a statement. “Instead, they were expelled from the country, left without means of subsistence and, in some cases, stripped of identity documents.”

One activist group has raised more than 245,000 euros (about $278,000) for the released prisoners, and Tsikhanouskaya said she’s asked Western governments for help.

“People went through real hell, and now we are working together to help them and facilitate their legalization and settlement, engaging all contacts with both American and European allies,” she said.

Bialiatski, Labkovich and five other members of Viasna, Belarus’ oldest and most prominent rights group, were arrested in Lukashenko’s crackdown on mass protests after a 2020 election that kept him in power and was denounced as rigged by the opposition and the West. Tens of thousands were arrested, with many brutally beaten, while hundreds of thousands fled abroad.

Along with Bialiatski, Labkovich was accused of “financing public unrest” and helping those affected by the crackdown. Bialiatski was sentenced to 10 years in prison; Labkovich got seven.

Prison authorities tried to coerce Labkovich to cooperate and launched two more criminal cases against him – refusing to obey orders of prison officials and high treason, which could have added another 15 years to his sentence.

Labkovich said he spent more than 200 days in solitary confinement and “and lost count of the nights on the concrete floor in the icy cell.”

Two other Viasna activists – Marfa Rabkova and Valiantsin Stefanovic – remain imprisoned. Labkovich believes they and others are still held so that authorities “can influence the behavior and statements of those released.”

Babaryka, 62, recalled that while in prison in 2023, he started having fainting episodes and once woke up with a broken rib, torn lung, pneumonia and 23 cuts in his scalp. He said he didn’t know what had happened while he was unconscious and didn’t want to elaborate on the conditions behind bars.

“I’ll tell you the truth: Those who come out shouldn’t talk about how they were and what they felt, because many people remain inside the system and depending on what they say, they will generally get disadvantages rather than advantages,” Babaryka said Sunday in Chernihiv, Ukraine.

His 35-year-old son, Eduard Babaryka, is among more than 1,100 political prisoners still held in Belarus, serving a 10-year sentence on charges of organizing mass unrest.

While prisoner releases have become more regular recently, Lukashenko’s crackdown continues, targeting critics wherever they live. Belarusians living abroad cannot renew their passports or get new ones at embassies and consulates, making life difficult for thousands who fled the repression.

Opposition activists, rights advocates and journalists in exile face criminal trials in absentia. Authorities seize their apartments and other property, with courts rejecting attempts to contest those moves.

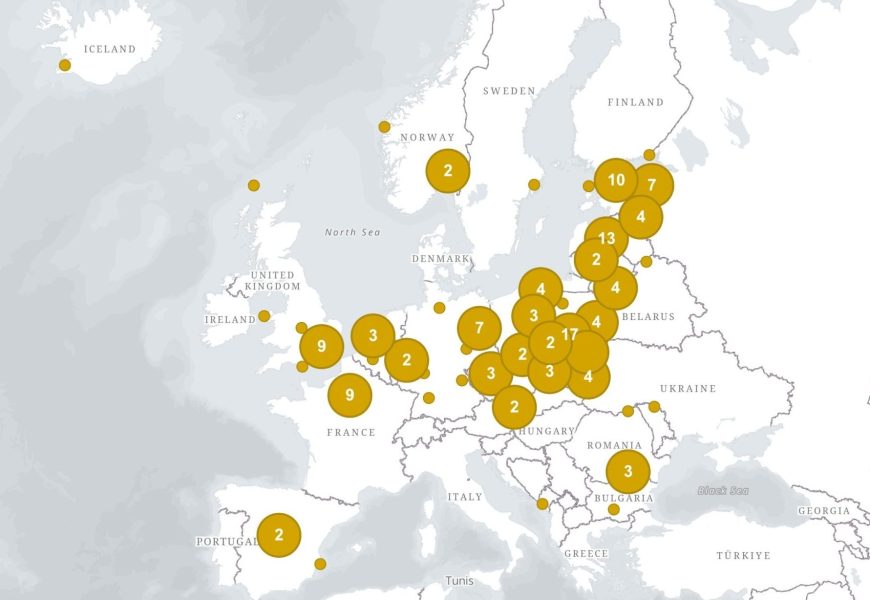

Activists say there is a “revolving door” of prisoner releases and arrests. Since the Dec. 13 release, Viasna declared seven more people to be political prisoners, and 176 since September.

Despite this month’s pardons, Amnesty International’s director for Eastern Europe Marie Struthers urged people not to forget those whose freedom “is long overdue.”

“If this release is a part of political bargain, it only underscores the Belarusian authorities’ cynical treatment of people as pawns,” she said.

Earlier this week, activist Aliaksandr Zdaravennau, 46, of the southern city of Rechytsa, was convicted of high treason and participating in extremist activities and sentenced to 10 years. Subway engineer Yury Karnitski, 44, and shop clerk Alena Hartanovich, 52, were added to the Interior Ministry’s list of extremists.

“While the prisoner releases are certainly a relief, there are no signs from Belarusian authorities of a change in the policy or practice of repression,” Muižnieks said. “Belarus continues to rank among the countries with the highest number of political prisoners per capita.”